The Kernel Contract: Why Logical Decoding Defined Core PostgreSQL Physics While pg_repack Remains the Apex Extension

I. Introduction: The False Equivalence of Ubiquity

In the PostgreSQL ecosystem, we often conflate “indispensable” with “core.” We look at pg_repack as a fundamental requirement for production life—supported across nearly every major managed service provider, from AWS RDS to Azure—and we wonder why the Global Development Group (PGDG) hasn’t simply merged it into the source. To be clear, it isn’t “pre-installed”, users must still explicitly invoke CREATE EXTENSION, but its availability is a widely supported option for bloat management.

Meanwhile, the infrastructure for Logical Decoding was integrated into PostgreSQL 9.4 and 10 with careful precision. This divergence isn’t about popularity or user demand; it’s about architectural entanglement. One feature redefines the database’s contract with durability and state (Logical Decoding), while the other is a brilliant orchestration of existing rules (pg_repack). Understanding this boundary—the unwritten criteria that separate “kernel physics” from “extension engineering”—reveals the underlying philosophy of how PostgreSQL manages data integrity versus operational utility.

II. The Durability Contract: Why Logical Decoding Required Kernel Authority

Logical Decoding was not merely a “feature” addition, it was a fundamental expansion of the PostgreSQL durability model. To achieve transactionally consistent data export, the engine had to expose its most internal mechanism: the Write-Ahead Log (WAL).

II.A. The Log Sequence Number (LSN) and the Physical Log

The WAL is the physical source of truth. It tracks changes using the Log Sequence Number (LSN)—a physical pointer to a specific location in the byte stream. Before version 9.4, the WAL was primarily a tool for crash recovery and physical streaming (byte-for-byte block replication), though it could be inspected in limited ways via tools like pg_xlogdump.

Logical Decoding changed the mission of the log. It required the kernel to transform physical byte-changes back into logical row-level events. This “decoding” cannot happen in isolation; the decoder must access the system catalogs (schemas and types) to interpret what those raw bytes represent. Because this process requires additional logical information to be retained in WAL records, it requires the wal_level to be set to logical, which is a cluster-wide promise about WAL content and retention. If a cluster is currently at a lower level like minimal or replica, raising it to logical necessitates a server restart to redefine the durability stream format.

II.B. The Gravity of Replication Slots

The mechanism for ensuring this stream is reliable is the Replication Slot. A slot is a persistent, crash-safe state tracker that ensures the primary server retains every WAL file starting from the slot’s restart_lsn.

This is where the architectural importance lies. A logical slot creates a physical dependency between an external subscriber and the primary server’s disk space. If a slot were managed by a less-privileged external utility, the kernel would have no reliable way to coordinate WAL retention with its own internal checkpointing process. By making slots a core kernel primitive, PostgreSQL ensures they are crash-safe—the slot’s state is persisted to disk during checkpoints—and the storage engine is bound to retain the data the subscriber hasn’t yet seen.

II.C. Transactional Snapshot Consistency

Creating a logical slot requires an EXPORT_SNAPSHOT to capture a transactionally consistent view of the database. The kernel must coordinate with the transaction manager and the Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) horizons to ensure the logical stream begins at a point where no uncommitted changes affect visibility. This level of snapshot orchestration requires hooks into the heart of the transaction manager—privileges an extension simply cannot safely hold.

III. pg_repack: The Mastery of the Extension Layer

If Logical Decoding is about redefining the rules of the system, pg_repack is about playing the game better than anyone else. It addresses the consequences of MVCC bloat (storage fragmentation and dead tuples) by using the stable, high-level APIs the kernel already provides.

III.A. The relfilenode Swap: A Masterclass in Catalog Engineering

A common technical misconception is that pg_repack performs an “OID swap.” In PostgreSQL, Object Identifiers (OIDs) are immutable identifiers for relations. Swapping them would break foreign keys and internal invariants.

Instead, pg_repack performs a relfilenode swap:

Trigger-Based Logging: It creates a temporary log table and installs triggers on the original table to record concurrent DML changes.

The Shadow Table: It creates a “shadow” table and copies the live data into it.

The Catalog Swap: In the final atomic phase, it updates the pg_class catalog to point the original table’s OID to the new table’s physical file (the relfilenode). It performs this swap for heap files, TOAST tables, and indexes simultaneously.

The Drop: It drops the old, bloated physical files.

The application never sees a change in the table’s identity (OID), but the underlying physical storage is replaced. This is “engineering”—orchestrating existing catalog primitives to achieve an outcome without requiring the kernel to change its fundamental storage physics.

III.B. The Reality of Locking

pg_repack is often colloquially described as “online,” but it is technically lock-optimized. During the long-duration data copy phase, it holds a SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE lock. This allows concurrent INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE operations but prevents conflicting DDL or maintenance operations like VACUUM FULL from interfering.

It only requires an ACCESS EXCLUSIVE lock—the kind that blocks all traffic—for very brief windows at the start (trigger setup) and the end (the relfilenode swap). Because this logic can be implemented using standard SQL and background worker infrastructure, it doesn’t “need” to be in the core, the extension API is already powerful enough to support it.

IV. The Philosophical Divide: System Contract vs. Operational Utility

The decision of what goes into the core reflects a fundamental boundary of responsibility.

IV.A. Failure Modes and Integrity

A flaw in Logical Decoding is a failure of the system’s contract with the truth. If the logical stream skips a transaction, your entire distributed ecosystem (CDC, replicas, microservices) becomes silently inconsistent. This risk necessitates the highest level of review and kernel integration.

In contrast, the failure mode of pg_repack is primarily operational. While a failed swap can leave behind leftover log tables or triggers that require manual cleanup, the original table and its data remain intact. However, in high-load environments, issues like insufficient disk space for the shadow table (requiring roughly twice the table size) or deadlocks during the swap could escalate to outages or require intervention. Because pg_repack relies on high-level abstractions, its failure does not compromise the fundamental transactional physics or the crash-recovery path of the database.

IV.B. Innovation and the Extension Laboratory

Leaving pg_repack as an extension allows the community to iterate faster than the PGDG core. We see this with pg_squeeze, which attempts to “replace” pg_repack by using Logical Decoding itself to handle the data copy instead of triggers. By utilizing the kernel’s logical decoding infrastructure, pg_squeeze reduces the overhead of capturing concurrent changes during a rewrite, though it comes with trade-offs like requiring wal_level=logical, replication slots (which can increase WAL bloat if lagged), and more setup complexity. This proves the value of the split: the kernel provides the “physics” (Logical Decoding), and the extensions provide the “engineering” (online bloat management).

V. Comparative Analysis and Conclusion

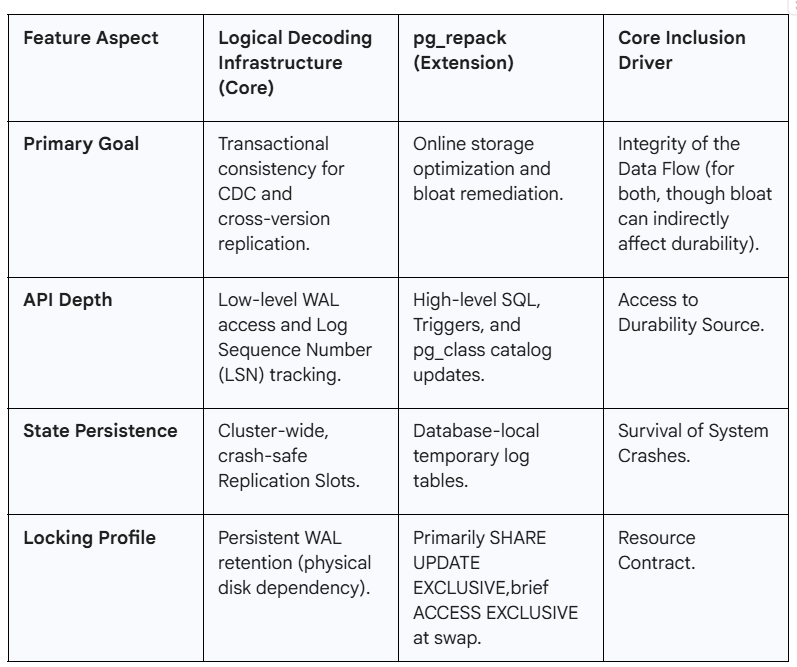

The distinction between these two tools is a textbook example of architectural prioritization.

Final Conclusion

The inclusion of Logical Decoding was a recognition that defining the data interchange contract—the reliable extraction of transactional changes—is a responsibility of the database kernel. It required deep entanglement with WAL management and MVCC visibility to guarantee the integrity of the data stream, a non-negotiable requirement for modern distributed systems.

By contrast, pg_repack validates the power of the PostgreSQL extension model. It solves a massive operational challenge (online bloat) by orchestrating existing rules—triggers, shadow tables, and relfilenode swaps—without needing to change the underlying physics of the engine. As we move into PostgreSQL 17 and beyond, with significant improvements to VACUUM memory efficiency via radix trees, the “apex” status of these tools may be challenged by the core engine’s evolution. But for now, the boundary remains clear: if it introduces new durability invariants that must survive crashes and upgrades, it belongs in the kernel, if it orchestrates the catalogs, it’s an extension.

Note that as of 2025, there is an ongoing patch proposal to add a REPACK command (potentially concurrent) to the core, which could shift this dynamic in future releases.

Mental Model for Architects:

If a feature requires a new way to guarantee durability or transactional visibility across the log, it belongs in the Kernel. If it can be achieved by orchestrating existing locks and catalog updates, it belongs in an Extension.

Open Question:

PostgreSQL 17’s introduction of radix trees for VACUUM dramatically reduces memory overhead, but it still marks space as reusable rather than returning it to the OS. Will the core engine ever internalize the “shadow table” strategy for a truly native, online VACUUM FULL?